Are we inviting clothes moths into our living and working spaces?

By Patrick Kelley, BCE

The full menu of clothes moth larvae includes dead rodents and birds.

Clothes moths are the number one pest in the world that consume and damage our clothing and rugs. Unknown to many, adult clothes moths do not eat, instead the larval stage of this damaging pest is the only one doing the damage.

When thinking about what clothes moth larvae like to feed on, materials such as feathers, wool, and fur come to mind.

While these materials can be food sources, the menu list for clothes moths expands to include dried and desiccated carcasses of rodents, birds, and other animals as well.

Hidden reservoirs of dead animals like these (inside or outside) give the moths a foothold to keep their populations high until they see a chance to invade our spaces and consume our belongings. By not actively seeking out and removing dead animals, we are more than likely inviting them into the spaces where we live and work.

Ironically, IPM specialists and pest professionals can sometimes use pest control measures that benefit the populations of clothes moths. Louis Sorkin, the renowned Board Certified Entomologist from the American Museum of Natural History (retired) stated this, “Pest Management Professionals, technicians, etc., forget where they place rodent traps, monitors, bait stations and those dead, dried corpses become prime larval feeding areas over time. They can be in somewhat inaccessible places. Anticoagulant rodent baits also contribute to potential larval food items when the rodents die in inaccessible (to us) places, but small moths and dermestids will find them.” Lou also backed up his comment by granting us permission to use a plethora of his images of clothes moths actively feeding on dead animal carcasses. You will those at the end of this article (Viewer beware: Some may find these images disturbing).

Imagine a mouse in a city environment that is living outside a museum or a residence. That mouse runs to a bait station box, strategically placed by a pest management professional, and consumes some of the toxic bait that was placed into that box to specifically kill it. After a few days, the mouse begins to feel sick. The mouse’s natural instinct in its weakened state is to find a quiet and protected space away from predators. Looking for safe harborage, the sick mouse locates and easily slips through a small ¼ inch

(6.35 mm) gap on the outside of the building and finds a void inside a wall. Here in the void, the mouse feels safe, but dies a few days later when the effects of the toxic bait finally reach a lethal level. Flesh- eating flies find the corpse quickly to consume the rotting flesh, but after one or two months, that dead mouse dries up and sits there. Six months to a year later, a lone female clothes moths (potentially from a resident population in the building) happens to find the dead mouse in that wall void and lays her eggs on it. Her 30 - 50 eggs hatch in a few days, and an infestation begins that can rapidly reach hundreds of moths searching for food sources to lay their eggs. When hatched, these hungry offspring will eventually find the collections being stored at the museum or will find your closet full of wool or your favorite Persian rug. Now imagine this scenario playing out in multiple locations around the museum or a residential building, while each and every dead mouse carcass is a prime food source for clothes moth caterpillars.

Individuals that set up and forget about mouse traps that they set and placed in rarely seen areas, can also lead to clothes moth and carpet beetle issues. I have also seen structural defects on the roofs of city buildings that allow birds to fly down into a crevice, get trapped there and die, where moths eventually find them.

Regardless of how a dead rodent or bird ends up in close proximity to people and their belongings, the fact that they are present, poses a risk that they will attract clothes moths and/or carpet beetles that can eventually cause serious damage. Understanding the complexities of this insect and its diet will ultimately help us control the amount of damage that it does.

Illustration by J. Crocker, taken from Rodent Control: A Practical Guide for Pest Management Professionals, with permission from GIE Media

Moths and caterpillars around a dead mouse on a glue board. Photo courtesy of Louis Sorkin, BCE

Clothes moth frass on a rodent carcass. Photo courtesy of Louis Sorkin, BCE

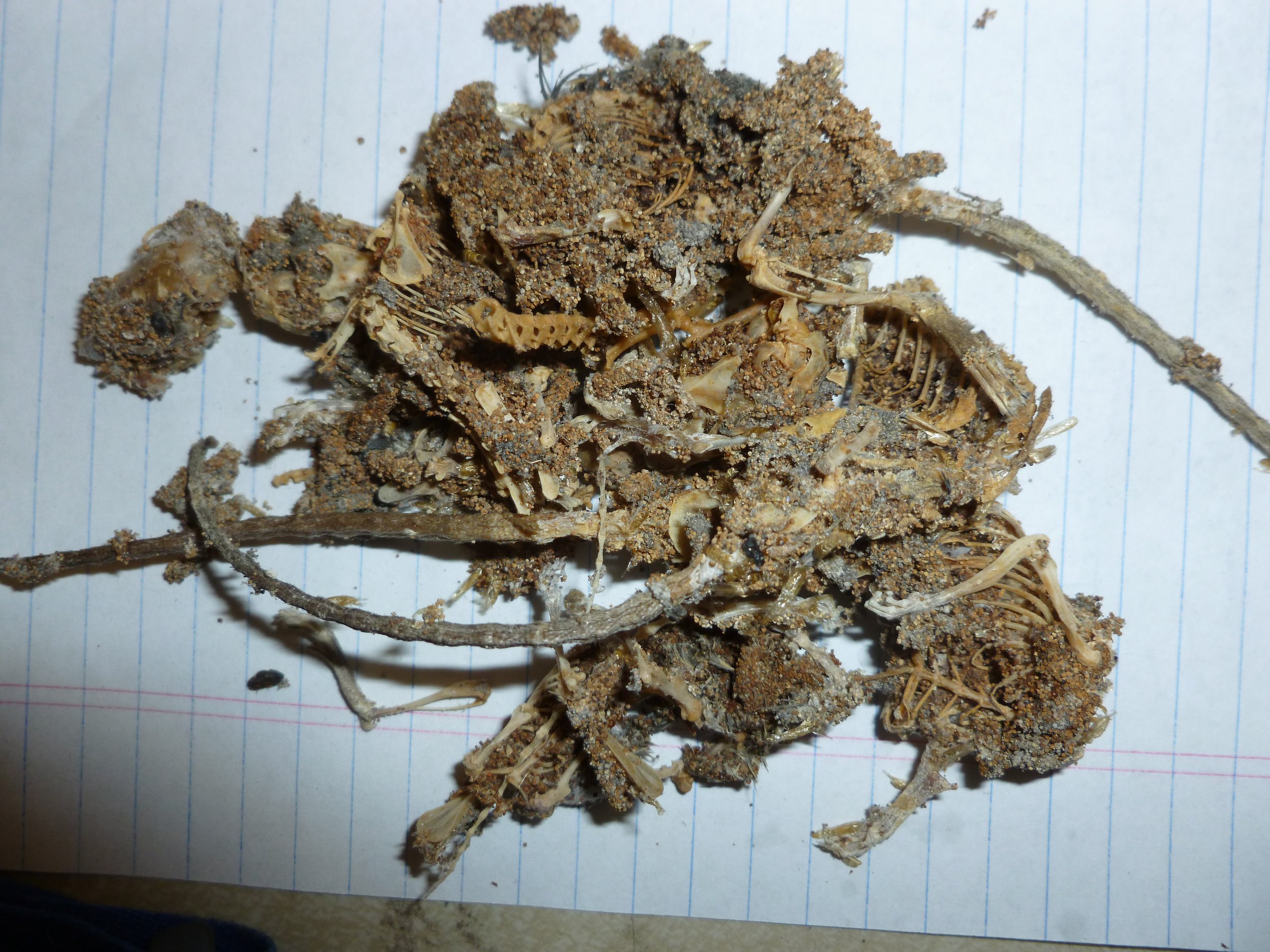

A completely consumed rodent carcass covered in webbing clothes moth frass and some empty pupae. Photo courtesy of Louis Sorkin, BCE

Clothes moths and dermestid beetle larvae have consumed the hide and hair from the rodent on the left. The image on the right also shows evidence of clothes moth and dermestid larval feeding alongside blow flies and sarcophagid flies and puparia. You can see these two mice on this glue board are earlier in their decomposition since there is more flesh and skin evident. Photos courtesy of Louis Sorkin, BCE.

**A very special thanks to Louis Sorkin, BCE for the ideas behind this article and the detailed images of clothing moths on dead and desiccated rodents.

Louis Sorkin, BCE showing off some live arthropods. Photo taken from https://twitter.com/AMNH/status/1115673710487375873, American Museum of Natural History, Twitter account April 9, 2019.

Insects Limited, an Insect Pheromone Company

Insects Limited, Inc. researches, tests, develops, manufactures and distributes pheromones and trapping systems for insects in a global marketplace. The highly qualified staff also can assist with consultation, areas of expert witness, training presentations and grant writing.

Insects Limited, Inc. specializes in a unique niche of pest control that provides mainstream products and services to protect stored food, grain, museum collections, tobacco, timber and fiber worldwide. Please take some time to view these products and services in our web store.